“Oh, I have a project due on Monday.”

This doesn’t surprise me. I’d been through this enough times with my older kids, now grown men, to be surprised by these sudden revelations. Hell, I’ve been through this enough times with Malcolm, already. The pattern was the same. The pattern was always the same. I no longer even lost my temper.

“That’s fine, Mal, but you know we’re in Baltimore for the weekend. We’re going to have to do it while we’re here. Do you have a supply list?”

“No. I left the information sheet at school.”

This is also no great surprise. We had tried various ways to keep Malcolm organized—reminder notes, a folder that stayed in his bookbag where he was to keep all his important papers so any needed information was always accessible, but the notes and folders always seemed to end up lost, or forgotten.

“But that’s okay, Freddie. I really only need one thing.”

“Oh, yeah? What’s that, kiddo?”

“Beads!”

Beads. That’s easy enough. Baltimore has an infinite supply.

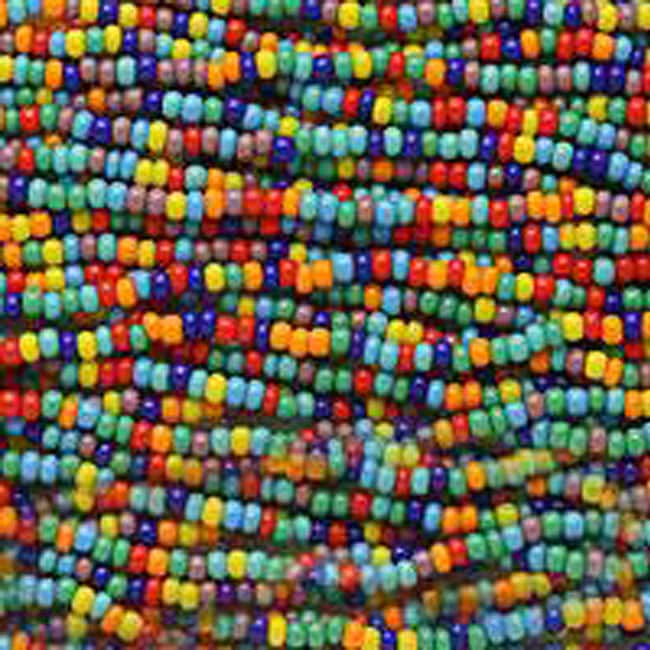

I think about taking him to Beadazzled, or one of the other high end shops stocked to the gills with a dazzling variety of the tiny plastic or glass jewels. They cater to the do-it-yourself, neo-bohemian spirit that had begun sweeping over the city years ago, when we realized that what we could create on our own would always be more precious than anything that could be found in a store. Granted, there is plenty of pre-made jewelry, as well, for those less creatively inclined, or those who have run out of time.

But the truth is that we were already headed uptown. To turn around now wouldn’t make sense. Admittedly, there’s the issue of cost, too. Some individual beads at the high end stores can cost more than what I have in my pocket, and I don’t want to spend too much on a project I have too little information about. There’s no point, especially when 33rd and Greenmount is so close.

“No worries, kiddo. I know exactly where to go.”

You can always tell when you’re getting close to the corner of 33rd Street and Greenmount Avenue at night because of the grim, red and blue glow illuminating the black sky. The city begins strategically setting up pairs of cop cars at the McDonalds at 29th Street, and they keep running up Greenmount, in pairs every couple of blocks, all the way up to 40th—a not so subtle attempt at a reminding the populace that the city is still in control.

It’s been that way since before the most recent uprising, and I imagine will remain that way for far longer. More important than reminding criminals who’s in control, it makes the residents feel safer, safe enough to come out and shop on a hot, summer night, where, without the lights, the shops would simply close at dusk, and the residents would stay cooped up inside, or spend their money outside their own neighborhoods.

Tonight must have been particularly active. The pattern of pairs had been broken, and there were several cop cars congealed right at 33rd, the red and blue lights flashing in a rabid, frenetic pattern on the streets, up the walls of the storefront rowhouses, out into the night sky. The sidewalks are lined with young black males lying prone on their stomachs, hands behind their backs, knees pressing into the gutters—lined up like tunas on a dock after a big catch.

“Just stick close to me,” I tell Malcolm as I sense his nervousness. I casually draw him closer, enough to comfort him, but not enough to offend his independent tween sensibilities. “We’re almost there.”

We enter the store, a lovely old storefront on the northwest corner made more beautiful by the sheer, seemingly endless mass of beads covering the display windows, the chaos creating a expressionistic mosaic wrapping around that corner, more elaborate than anything Pollock could have concocted. Even Malcolm is agog at the immensity of it all—or he would be if the drama outside the doors hadn’t have bled inside.

One of the narrow aisles is blocked with several police officers, knees, hands and feet busy into the backs and necks of three young black boys, none of them older than Malcolm, their pockets bursting with stringed beads. I can’t help but to think why so many officers are needed to subdue three children. One of the officers, a sergeant, barks at us to wait. I recognize him. We went to high school together.

One of the narrow aisles is blocked with several police officers, knees, hands and feet busy into the backs and necks of three young black boys, none of them older than Malcolm, their pockets bursting with stringed beads. I can’t help but to think why so many officers are needed to subdue three children. One of the officers, a sergeant, barks at us to wait. I recognize him. We went to high school together.“Garrity, right?”

He looks at me quizzically. “Do I know you?”

“Yeah! We came out of Poly the same year.”

“French Fry?”

“Yeah, but nobody calls me that, anymore.”

“Right. Sorry about this. Things are crazy, you know.”

“ I can see that, but these are just kids, though.”

“Yeah, well, a dog is just going to grow into another wild animal if you don’t train them right.”

I don’t know how to respond to that.

“Is that your kid?” He asks, snapping his chin at Malcolm.

“Sort of,” I reply, “he’s my stepson.”

“Well, keep him safe,” he advises me, “and keep him away from these animals.” Garrity stretches an arm out, as if to protect us from the danger of the three boys now being dragged out of the store, hands zip-tied behind them, pockets still bulging with cheap beads. Once they are out, he looks back at me. “Nice running into you,” he says as he follows his squad and quarry back onto the streets.

Now that the store is clear, I let Malcolm loose, tell him to pick out what he needs. While he does, I can’t help thinking that the only thing separating Malcolm from the kids we just watched getting dragged out, aside from location and upbringing, is that no one can tell Mal is black just by looking at him. I wondered how he would be regarded, how he would be treated, if his skin showed more of the truth.

“I can’t find anything.”

“What do you mean, kiddo? Look at all these beads!”

“I know, but these are all on strings. They already have their patterns.”

I don’t understand, but he doesn’t have his assignment sheet, so there’s nothing for me to reference. “That’s okay, kiddo. There’s a store I can take you to tomorrow where the beads aren’t already on strings. We’ll try again, tomorrow.”

We walk out and cross Greenmount. There, Malcolm sees a kid he recognizes. Carlos, a boy he had gone to school with when we still lived in the city. He was carrying fistfuls of stringed beads. I stop to let them talk, a chatter I can barely understand, but soon enough they are on the ground going through Carlos’ collection. I hear a light pop, followed by an explosion of beads up in the air and hitting the sidewalk like plastic rain. I go to interfere, thinking this is the result of some unwarranted tug of war, but stop myself when I notice that the are still happy, still laughing.

We walk out and cross Greenmount. There, Malcolm sees a kid he recognizes. Carlos, a boy he had gone to school with when we still lived in the city. He was carrying fistfuls of stringed beads. I stop to let them talk, a chatter I can barely understand, but soon enough they are on the ground going through Carlos’ collection. I hear a light pop, followed by an explosion of beads up in the air and hitting the sidewalk like plastic rain. I go to interfere, thinking this is the result of some unwarranted tug of war, but stop myself when I notice that the are still happy, still laughing.I watch as they both sweep the beads together with their hands, create a mosaic, right there, on a 33rd Street sidewalk stained with years of grease, sweat and blood. After a while, the mosaic becomes a pile, and the beads are all gathered and poured into a clear plastic bag.

“You want some?” Carlos asks Malcolm.

“No, that’s okay,” he replies, before Carlos takes off running in some seemingly random direction.

“Freddie, is the store still open?”

I look behind us. The lights are still on. “I think so, kiddo.”

“Can we go back? I think I know what I need now.”

“Good!” I say as we head back to Greenmount, “let’s try it, again.”